Virginia is so steeped in history and natural beauty that it boasts some of the most popular tourist destinations in the country. I genuinely enjoy exploring all of our state’s must-see attractions, but it is sometimes even more rewarding to visit newer, quieter gems. That is just one of the reasons why I was so charmed by our recent visit to Machicomoco State Park.

Our 40th state park and one of the newest parks in the system, Machicomoco opened in the spring of 2021, two years after its ceremonial ground breaking. Boasting 645 acres, Machicomoco State Park is situated in Hayes, VA on the Middle Peninsula, about 8 miles from Yorktown (read my recent blog post about family-friendly activities in Yorktown here). The park itself is a peninsula, bordered by Cedarbrush Creek to the northwest, Timberneck Creek to the southeast, and Poplar Creek and the Catlett Islands to the south, just before all three of the aforementioned creeks flow into the York River. Machicomoco is home to a little over 6 miles of trails, as well as a campsite, yurt rentals, a boat launch, and a couple of scenic overlooks.

Upon entering the park, we were greeted by a friendly ranger that pointed us in the direction of the Interpretive Area, which is what I was most excited to see. The Interpretive Area highlights Machicomoco’s commitment to honor the stories of the Indigenous people who inhabited the area for thousands of years before the arrival of British colonists. In fact, local Indigenous people participated in the design of the park and helped come up with the name, which is means “a special meeting place” in Algonquin. The historic roots of the region run deep – the park is just 10 miles from Werowocomoco, the village that served as the political and spiritual headquarters of Chief Powhatan. Note that though Werowocomoco is now owned by the National Park Service, it won’t be open to the public for some time. However, the nearby Gloucestor Visitor Center has a permanent exhibit dedicated to this important historic site.

Our first stop upon arriving at the Interpretive Area was the timeline embedded into the pavers. This timeline tells the story of thousands of years of Indigenous history. Regional colonial history is also woven in, but its very late starting point in the timeline really drives home the length and profundity of Indigenous presence in the area.

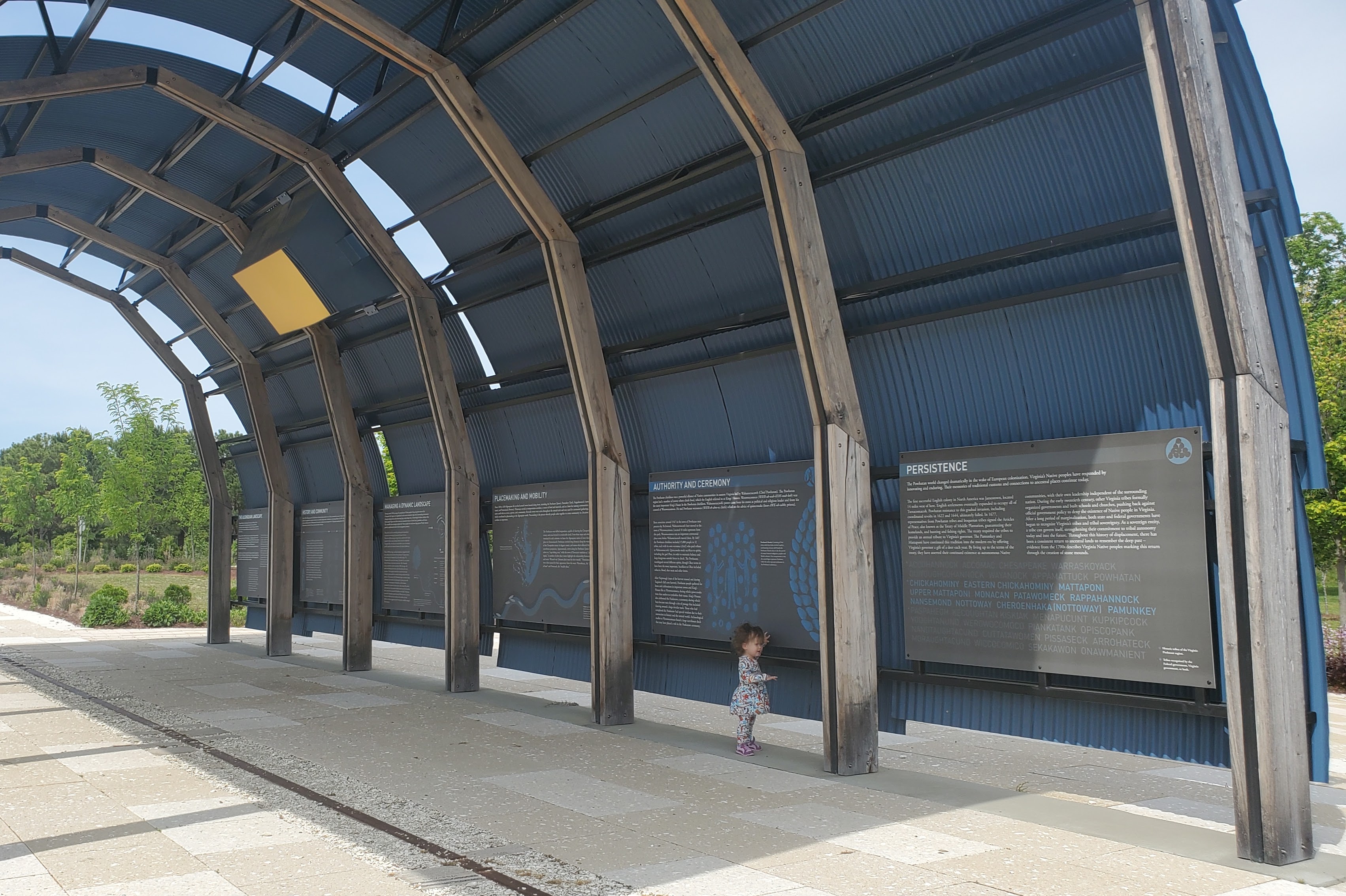

The girls and I took our time walking along the timeline. I read each paver out loud, and Daughter #1 and I discussed the different events while Daughter #2 ran her little fingers over the shells that lined the exhibit (a reminder of the importance of oyster harvesting to historic Indigenous populations). When we reached the end of the timeline, we found ourselves in a replica of a traditional longhouse. Though the longhouse has modern touches to help it withstand the elements for years to come, its beams are made of black locust tree wood, which is an authentic material in longhouse construction. The longhouse is lined with panels that share more information about local Indigenous cultures and traditions.

Next to the longhouse is this stone map of the region, which denotes the ancestral homes of dozens of Indigenous populations.

Once we finished exploring the open-air exhibits, we took the nearby trail down to the water. This trail meanders through a field of tall grasses until it reaches a break in the tree line. There, a small dock awaits visitors.

The dock is a remarkably peaceful place to take in the scenery and listen for local wildlife.

Along the dock we spotted posts with images burned into them. The images are significant to the area and to local Indigenous cultures. The dock beams list the names of each image in both English and Algonquin. The language teacher in me absolutely loved this feature!

The grasses growing out of the water are home to Periwinkle snails. I remember learning during our kayak ride near Cape Charles that Periwinkle snails can spend their entire lifetimes traveling up and down the same single blade of grass. I don’t know if it’s due to the vastness of the universe or the occasional monotony of daily life, but I think about this fact often.

Overall, I was really impressed with Machicomoco State Park’s dedication to celebrating the Indigenous peoples whose narratives are so deeply woven into the fabric of the Chesapeake watershed. Machicomoco is not the biggest or flashiest site in the state, but its simple beauty and historic and cultural significance are reasons why I think everyone should visit this sweet park. For more information and details about Machicomoco State Park, consider reading this news article or watching the video below. To plan a visit that coincides with Indigenous-specific events or programing, check out these descriptions of an NPS pop-up program called Indigenous & Colonial Watermen of the Chesapeake, an opportunity to learn how to make pinch pots, and a one-of-a-kind Indigenous People’s Celebration.

Have you visited Machicomoco State Park yet? What did you think? Please let me know in the comments!

One thought on “Machicomoco State Park”